.png)

What is the Galileo Fallacy?

People

defending an extraordinary claim often refer to their heroes as

modern-day Galileos. The argument comes in different forms and

sounds a bit like this: "He is being persecuted by the establishment, just as Galileo found himself opposed

by the establishment". Most of the instances of this argument are actually fallacies, as I will attempt to show.

High dilutions

I will first show that defenders of the following case invoke the Galileo Fallacy and then I will show how it is not comparable to the case of Galileo (using a bit of a Bayesian perspective).

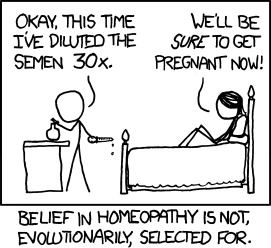

The case is that of Jacques Benveniste and his claim to fame within the homeopathy community. As you perhaps know, homeopathic 'remedies' are so diluted that they physically do not contain any element of the diluted substance. So there is actually nothing in it (pun intended). Jacques Benveniste published an article in Nature in 1988 claiming that human white blood cells react to substances that highly diluted that there is probably no molecule left in the solution. Sir John Maddox (then editor of Nature) agreed to publish the article if they were allowed to send a team of investigators to the Benveniste lab to find out how they got this remarkable result. The investigation was filmed by the BBC program Horizon. In the end the team found that the cell-counting procedure was not blinded properly and after proper blinding the effect disappeared.

Still, some people think Benveniste was right and claim he was "too far ahead", as Nobel laureate Luc Montagnier said in an interview in Science. The French Nobelist actually calls Benveniste a modern Galileo, so this is a perfect example of the Galileo Fallacy. But why should this be regarded as a fallacy and not a proper argument?

The case is that of Jacques Benveniste and his claim to fame within the homeopathy community. As you perhaps know, homeopathic 'remedies' are so diluted that they physically do not contain any element of the diluted substance. So there is actually nothing in it (pun intended). Jacques Benveniste published an article in Nature in 1988 claiming that human white blood cells react to substances that highly diluted that there is probably no molecule left in the solution. Sir John Maddox (then editor of Nature) agreed to publish the article if they were allowed to send a team of investigators to the Benveniste lab to find out how they got this remarkable result. The investigation was filmed by the BBC program Horizon. In the end the team found that the cell-counting procedure was not blinded properly and after proper blinding the effect disappeared.

Still, some people think Benveniste was right and claim he was "too far ahead", as Nobel laureate Luc Montagnier said in an interview in Science. The French Nobelist actually calls Benveniste a modern Galileo, so this is a perfect example of the Galileo Fallacy. But why should this be regarded as a fallacy and not a proper argument?

Prior odds

In looking

if the argument is justified I would like to take a bit of a bayesian approach.

All that means is that I am going to look at the prior evidence. Let's take a simplified look at Bayes' rule:

prior odds x likelihood ratio = posterior odds

or

previous factual belief x new evidence = revised factual belief

prior odds x likelihood ratio = posterior odds

or

previous factual belief x new evidence = revised factual belief

It shows how you should change your belief to the availability of new evidence, but it relies crucially on prior evidence or odds. If we now compare the case of Benveniste with the case of Galileo we see that the prior odds in both cases differ. In the 17th century Galileo provided new evidence that should be evaluated against the prior odds or previous factual belief (geocentric model). The evidence for the geocentric model was quite weak, thus new evidence has a high chance of updating or revising the factual belief. But this update of belief was exactly the thing that was opposed. If we are to look at the case of Jacques Benveniste and regard the prior odds, we can see that these have to be very high. If Benveniste's findings were true, we should take a long and hard look at the foundations of physics, chemistry, medicine, pharmacology, etc., because these would be highly incorrect. Thus, I would state that due to the difference in prior odds the case of Benveniste is in no way comparable to that of Galileo.

Finishing, I think Tim Minchin states the prior odds of Benveniste's research most impeccably in his beat poem Storm when he proclaims:

It's a miracle! Take physics and bin it!

Water has memory!

And while it's memory of long lost drop of onion juice is infinite

It somehow forgets all the poo it's had in it!

You show me that it works and how it works

And when I've recovered from the shock

I will take a compass and carve Fancy That on the side of my cock

Reacties

Een reactie posten